Voting With Your Pitchfork: Beyond the Consumer-Worker Binary

Why we need to go beyond conscious consumption to transform the food system

By Austin Bryniarski, a food systems researcher and writer who worked at the Public Justice Food Project (now FarmSTAND) as a Research Paralegal.

As the food movement took shape about two decades ago, so did one of its many pieces of advice: “vote with your fork.” The idea was simple and seductive. Three times a day, you could decide what to eat, consistent with your values and aspirations for the food system. Slowly but surely those decisions would sync up with other “conscious consumers” and aggregate into a food system that could become good, clean, and fair.

With a healthy amount of hindsight, many who work in food systems change now understand the shortcomings of this way of thinking.

For example, the reporter Sarah K. Mock offers a succinct summary for why voting with your fork is “total nonsense.” Ethical shopping is expensive and inaccessible, requires an impossible amount of information, is easily co-optable by corporate interests, and is not scalable in ways that compete with the biggest of Big Food players. In the end, Mock advises to “keep going to your local farmers market” if you want, “but not just as a shopper/consumer.”

That advice is sound because, as much as our current food system would have us believe that we are all primarily and merely consumers, other roles we play — as workers, advocates, and community members — offer much more effective avenues we can take to organize for a just food system. Further, the focus of the food movement on consumption, particularly regarding the environmental and public health harms of the food system, the role and experiences of workers in the food system — who are also consumers — is made invisible. In fact, ever-consolidating corporate actors benefit when we passively accept the idea that we are solely consumers, so resisting that frame — or at least engaging with it strategically — is important to our work.

At the Food Project, we’re working to critically engage with the idea that ethical consumption is all it takes to transform the food system. We use legal tools designed to protect consumers in a way that also protects workers. We frustrate the vote-with-your-fork logic and push back against narratives that pit consumers against workers, particularly as such a false binary persists in food movement efforts. Addressing corporate consolidation in the food system requires undoing this false binary; this blogpost offers some ideas and examples from the Food Project’s work to help us get there.

Consumers Above All

Biologically speaking, we have always been consumers. But the “consumer” at the center of the universe in which voting with your fork makes sense is a relatively recent invention.

Critiquing the idea of “the consumer” in 1850, the philosopher Karl Marx wrote about how the consumer identity makes it harder to observe power dynamics in society. He used the grocery store as an example. A business owner enters the grocery store and pays for food with money that came from his profits, while a worker enters the store and pays with money she got from her wages. Since they’re buying similar things at the same grocery store, they both appear to be consumers. As the scholar Michael Denning summed it up, “the class division between them is erased because they all seem to be consumers.”

What might it mean for the movement against industrial animal agriculture to see consumers and workers as one and the same?

Throughout the twentieth century, the figure of the consumer would only get stronger, as many people in the U.S. came to see themselves first and foremost as consumers, obscuring their roles as workers. This would have important consequences for organizing, as consumer movements of the 1960s and ’70s took political action through boycotts and other means of consumer activism through newly founded organizations like Public Citizen, the Consumer Federation of America, and eventually even Public Justice. As organized consumers, these groups made demands for product safety, worker safety, and environmental protection, at once strengthening government regulations while being skeptical about the role of government in society. (The historian Paul Sabin argues that this very skepticism has hamstrung bringing about ambitious, big-government visions like the Green New Deal or Medicare for All today.)

Not all interpretations of the consumer identity have been as positive. One example from the law is the concept of “consumer protection” in antitrust. Since around the 1980s, whenever the government has had to decide to intervene in big business mergers, it has been guided by a goal to keep the price of goods low for consumers. This idea of “consumer protection” being equated with low prices has shaped regulatory bodies like the Federal Trade Commission, and is the historical product of collaboration between economists and a well-organized business lobby. We see this logic appear in debates about consolidation in the food system, where a few firms can produce great quantities of cheap food and evade antitrust enforcement, despite all of the environmental, labor, and social harms of consolidation. While the food movement has historically demonized “cheap” food and the people who eat it, it is decades of agricultural exceptionalism, union-busting, and militarized immigration policies — abetted by consolidated corporate interests — that keep wages low and make cheap food necessary.

But a narrow definition of consumer interests, and what’s beneficial to workers, need not be at odds. “The idea, beloved by mainstream economists, [is] that the interest of workers and consumers are essentially a seesaw: for one to gain, the other must lose,” Christine Berry wrote last year in the Guardian. This is certainly the case in the food policy arena, where worker pay and protections are frequently met with warnings of higher food prices for restaurant-goers, or where ideas about food safety or various environmental certifications narrowly focus on product quality and not occupational health. Berry continues: “This conveniently ignores the third actor in the equation: the owners,” who have the power to set both wages and prices, handed that power by decades of deregulation and union decline. Yet we know from Marx’s grocery example that “workers and consumers remain the same damn people,” as reporter Sarah Jaffe once proclaimed.

So what might it mean for the movement against industrial animal agriculture to see consumers and workers as one and the same?

Post-Consumer Food Movements

It can be easy to write off “consumer” as a category, especially since “the consumer” and preserving consumer choice has been weaponized by all kinds of industrial titans to evade regulation. The scholar Luke Herinne offers a crucial reminder: “the consumer interest is always a matter of interpretation, and interpretation is always embedded in history. Workers are also consumers, and vice versa.” In this spirit, looking at some of the Food Project’s docket helps us see how the creative use of what looks and feels like consumer law can support fighting for worker rights and breaking up Big Food.

Twice now, the Food Project has used a District of Columbia consumer protection law to hold meat companies accountable for misleading advertising claims. The Food Project sued both Hormel and Smithfield for deceptive claims about “naturalness” and meat shortages, respectively. In either case, and especially in our case against Smithfield, how workers get treated by these highly-concentrated companies has been an important part of the litigation in different ways and at different steps.

We unveiled discovery materials from our false advertising lawsuit against Hormel Foods to show how the company’s abusive practices harm both consumers and workers.

Litigation that marries concerns about (often consumer-focused) food safety and worker safety have also been a mainstay of our work. While food safety has historically been concerned with food quality, fears of food fraud, and illness that results from contamination, our work recognizes that worker protections help keep food safe in important ways. Our work to fight back against the meat industry’s and government’s push to speed up production lines accounts for the effects such speed ups have on food quality and worker safety. For example, the inspection reports that we uncovered in our Hormel case illustrated how undue pressures on workers to work more quickly resulted in food safety violation after food safety violation. The amicus briefs we filed on behalf of elected officials that clarified the public health threats of ramping up linespeeds, and in the Supreme Court in support of Proposition 12, both illustrated how focusing on worker protection issues “trickle down” to protecting public health more broadly.

This has only become more important with COVID-19. At the outset of the pandemic, meatpacking workers were not given adequate protections against COVID-19 throughout the pandemic in pursuit of corporate profits, and those plants became supercharged engines for community spread of disease. More broadly, environmental litigation we’re developing that takes full account of how slaughterhouses affect workers not only where they work but where they live and play too is especially sensitive to how “worker” and “consumer” are roles one plays throughout the day as opposed to rigid and competing interests.

Our ag-gag work has also creatively frustrated the consumer-worker binary. Laws that penalize people for entering and filming meatpacking and other animal agriculture facilities in an effort for transparency are often couched in consumer-centric ideas about having a “right to know” what’s in one’s food. Agribusinesses lobby for these ag-gag laws to maintain secrecy around how food is produced. And while ag-gag litigation itself has a complicated history that has at times pitted precarious workers against animals — with little to no accountability for meat company executives in the C-suite — these moves toward transparency can help galvanize pro-labor organizing akin to the muckraking journalism of The Jungle. In this vein, the Food Chain Workers Alliance (FCWA) has been a plaintiff on our ag-gag case in Arkansas.

Finally, where our work aims to make markets fairer and more competitive, we move well beyond the threshold of “consumer protection” as equated with keeping meat prices low, especially since farmers, ranchers, farmworkers, and others are uniquely harmed by consolidation in the food system. In the chicken industry, whose tournament system pits producers against each other in a modern-day version of sharecropping, we represent producers harmed by the anticompetitive practices of corporations like Tyson who are calling for more vigorous enforcement of our country’s antitrust laws. In the beef industry, whose consolidation and market power has made it harder for specialty, high-quality ranchers to distinguish their product from generic, commodity beef, we have represented independent ranchers through the Ranchers and Cattlemen Action Legal Fund fighting against the Beef Checkoff program that tilts resources away from a system that disincentivizes high-quality production methods. Consumer interests are vast and varied beyond low price, and our work reflects that expansiveness.

Corrective Action Towards Collective Action

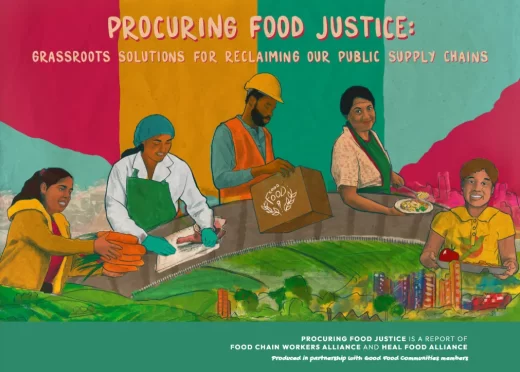

HEAL Food Alliance and Food Chain Workers Alliance’s recent report Procuring Food Justice offers a vision of how grassroots organizing can push institutional procurement policies to align with community values.

Reclaiming more progressive interpretations of consumer protection is not to say that a consumer-based prescription like “voting with your fork” is automatically a pro-worker act because consumers are workers. Rather, it’s an acknowledgement that focusing so much on consumer rights and protection as the central concerns of decision-making in how the food system should work draws attention away from thinking about forms of collective action — political advocacy, labor organizing, building and expanding localized systems of growing and distributing food, etc. — that have the potential to transform food systems. Collective action addresses the very structural imbalances of power that make food systems so harmful in so many different ways, while improving consumer behavior does not.

Many of our partner organizations sprang up in the prime of the mainstream, consumer-focused food movement from which the perspectives and demands of workers were excluded, despite having long been the vanguard of positive food systems change. For example, the Food Chain Workers Alliance, which we’ve represented in court, and the HEAL Food Alliance (the “L” stands for labor!), of which we are a member, both critically center the importance of building worker power to taking on corporate control of food and land. In their recent report Procuring Food Justice, FCWA and HEAL talk about how grassroots organizers can push institutions to buy food based on community values, channeling funds into suppliers that advance racial equity, workers’ rights, climate justice, and transparency and away from those that don’t. In other words, demand-side interventions can go hand-in-hand with workers’ rights.

Other groups have creatively expanded what consumer-driven change might look like, beyond the quiet choices we make in the supermarket aisle, bringing demands for change to the streets, college campuses, and communities. In response to dubious self-regulatory schemes like corporate social responsibility, in which corporate actors set their own internal benchmarks, metrics, agendas, and strategies for doing the right thing, organizations like the Coalition of Immokalee Workers and Migrant Justice / Justicia Migrante have developed their own models under the banner of “worker-driven social responsibility” (WSR) to reflect the knowledge and needs of those closest to corporate harm. This model activates consumers in ways that build solidarity across the food supply chain and politicize the otherwise apolitical identity of “consumer” to generate collective action like boycotts and other attention-grabbing campaigns that exert pressure on corporate actors.

These groups draw on longstanding movement tactics that aim to redeem the role of the consumer in food systems change. Check out their work and ours to see how blurring the lines between worker and consumer offers effective routes to food systems change.