Deep Dive: Hormel

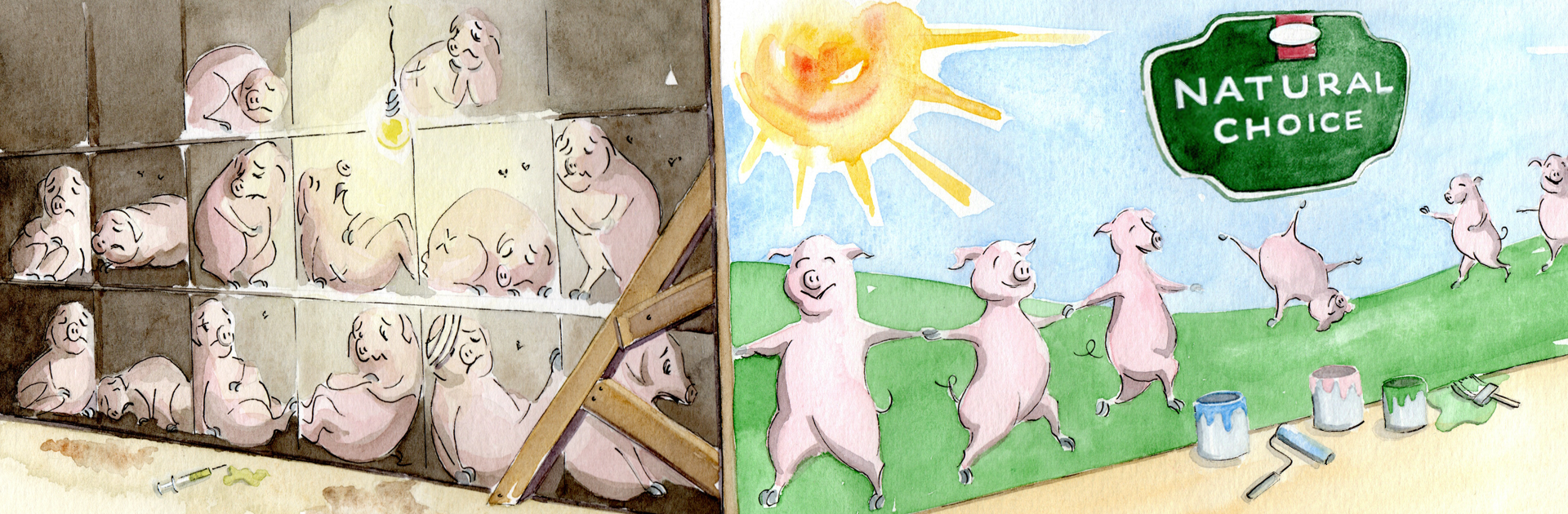

Hormel wants you to make the “Natural Choice.” Documents we’ve made public reveal how that is anything but.

In 2014, Hormel Foods Corporation celebrated the performance of one its fastest growing brands, “Natural Choice,” in its annual report. According to Hormel, Natural Choice-brand lunch meats and bacon were intended to resonate with the growing consumer segment of “wellness seekers” or customers “looking for better for you options” (Exhibit 5). To maximize this line’s growth, Hormel invested in a relaunch marketing campaign beginning in May 2015, urging consumers to “Make the Natural Choice” (Exhibit 1).

But the Natural Choice line was made of the exact same meat used in Hormel’s standard products, like Spam, misleading consumers into thinking their purchases benefited their health, the environment, and animal welfare more than buying other Hormel brands might. So in 2016, we sued. FarmSTAND (formerly the Food Project at Public Justice) brought suit with the Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF) in a Washington, D.C. court contending Hormel’s “natural” advertising was false and misleading. ALDF, Tracy Rezvani, and the Richman Law Group also acted as counsel in the case. Over the course of the lawsuit, a Hormel official confirmed that when people purchase Natural Choice products, they’re getting animal products that are no different than those that make up other product lines (Exhibit 207).

Consumers want to shop in ways that align with their values, but the lack of transparency in labeling and advertising poses a major barrier to doing so. This deep dive introduces revelations—many in Hormel’s own words—about the severity of Hormel’s factory-farm practices and the extent to which Hormel sought to deceive and take advantage of customers in marketing its line. This lawsuit’s discovery process shined a spotlight on previously inaccessible materials that paint a damning picture of industrial meat products like Hormel’s and the branding used to sell them. What follows are key insights about Hormel that showcase these materials, which offer entryways to take on the food industry at large through suits, organizing campaigns, and investigations.

There’s no segregation specifically done for Natural Choice Products.

— Deposition of Cory Bollum, Hormel, Exhibit 208

The extent to which Hormel researched, analyzed, and exploited consumer perception was more manipulative than previously understood.

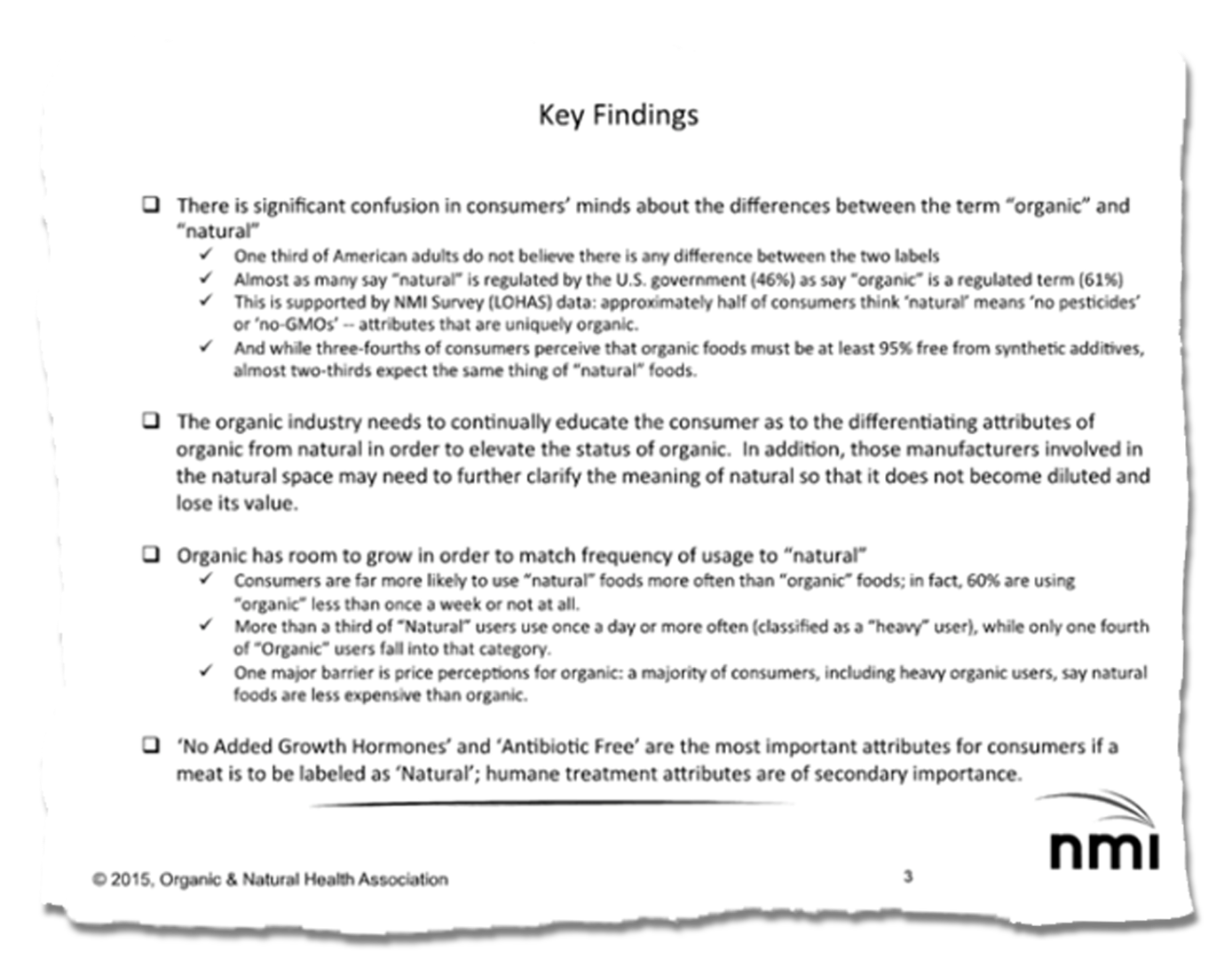

When you see the word “natural” on a label, the food industry knows the assumptions you make about the food you buy. But that doesn’t guarantee what you’re buying meets those expectations. According to former Natural Choice Brand Manager, Jeremy Zavoral, consumers who see a product with a ‘natural’ claim “assume that there are other benefits to the product” (Exhibit 218). Research shows that most consumers who heavily buy ‘natural’ labeled products believe that “natural” means that animals raised for food are humanely raised, grown free range, given no added growth hormones, and antibiotic-free (Exhibit 51). The crux of the suit was that Hormel’s ads “tend to mislead because the animals are born, raised, and killed in unnatural, unsafe, and cruel conditions,” conditions which “do not comport with reasonable consumers’ perceptions of ‘natural’ meat.” A fuller accounting of the discrepancy between the Natural Choice campaign and the realities of Hormel’s practices the case sought to prove are outlined in the complaint.

It is not surprising that corporations invest in consumer behavior and market analysis research to better hawk their products. Entire industries and academic disciplines exist to understand how to prime consumer demand and exploit the beliefs of would-be customers to compel them to purchase one product over another, or a product they wouldn’t otherwise buy.

What is surprising is the extent to which U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulations allow Hormel and companies like it to create confusion and misunderstandings that lead consumers to believe their products have qualities they do not. Looking at the company’s own documents, Hormel’s Natural Choice product line is tailor-made to take advantage of the popularity and interest in “‘Natural/Green/Healthy/Organic’ options” (Exhibit 5) by exploiting lax regulations surrounding the term “natural” to offer a product that was less expensive than one actually raised in “natural” settings – like free range versus factory farm conditions – and possessing the qualities consumers expect a “natural” product to have (Exhibit 51). In response to consumer feedback that nearly 95 percent of consumers wanted natural products accessible during regular shopping trips (Exhibit 1), Hormel put resources into changing their branding to green rather than brown, to communicate “natural” more (Exhibit 212). The following sections reveal that Hormel did not put similar resources into putting practices into place to produce food that consumers would reasonably consider to be more natural.

A: We had a brown version and we went with the green because it went better — it was seen as fitting more with the brand.

Q: So communicating natural more?

A: Communicating Natural Choice more, yes.

–Deposition of Karen Kraft, Hormel Foods, discussing label and advertisement presentation, Exhibit 212

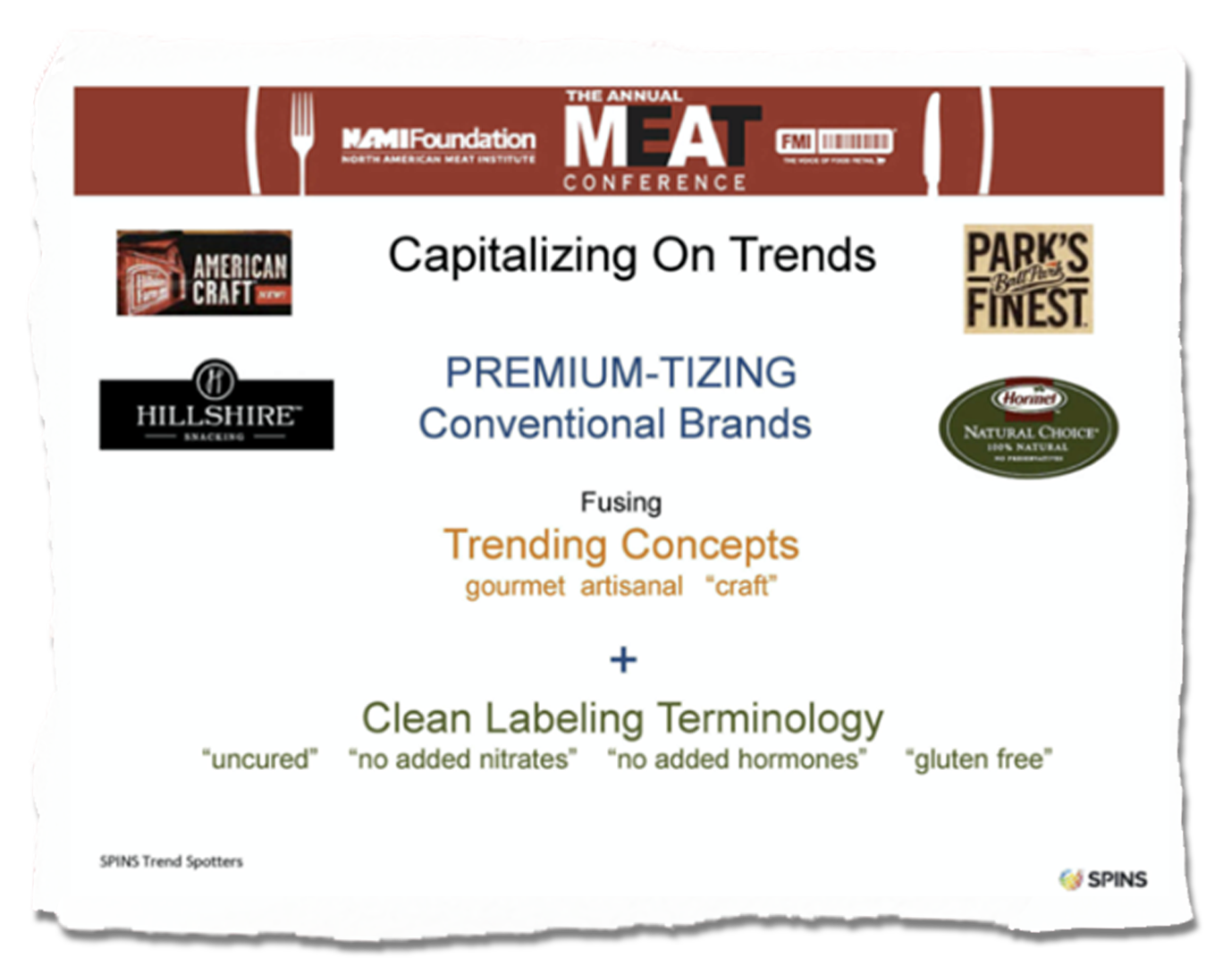

The deceptive use of the term “natural” is not unique to Hormel. In fact, Natural Choice advertising was put on a pedestal in a trade association slideshow as exemplary of the direction in which the entire industry might go. A meat industry slideshow produced by SPINS, a marketing company that specializes in promoting natural products, coined this “premium-tizing conventional brands,” in which otherwise unremarkable products are labeled in ways that combine trendy concepts (like “gourmet” or “artisanal”) with “clean labeling terminology” to appeal to “the natural meat customer,” including consumers who specifically want organic foods as well as people who want to eat healthier (Exhibit 37).

The same slide deck plainly says, “the term ‘natural’ is practically unregulated and can/will be used widely” (Exhibit 37). Yet another industry presentation from the Natural Marketing Institute found that “the high degree of consumer confusion is evident across many perceptions, including one in three who do not see a difference between ‘Natural’ and ‘Organic’ and government regulation for these labels” (Exhibit 51). This is especially problematic given that “organic” is a production certification that is regulated by the government and requires businesses to adopt specific practices and undergo inspections to verify the use of those practices.

An internal media guidance document for the rollout of the Natural Choice rebrand spells out the key messages Hormel developed to imply certain characteristics of Natural Choice lunchmeat. Media guidance documents often prepare employees to provide canned answers to frequently asked questions, including ways to address or sidestep controversial issues. In the guidance provided on the topic of “Animal Care,” Hormel has “a zero-tolerance policy for inhumane treatment of animals,” for example, with no further explanation. The guidance also spells out ways to pivot from questions like “The campaign emphasizes no preservatives; however, many of the Hormel Foods brands do contain preservatives. What would your response be to questioning consumers?” without addressing whether Natural Choice products contain preservatives (Exhibit 1).

Hormel’s apparent commitment to training employees to be opaque about Natural Choice products highlights the active role corporations play in creating consumer confusion and exploiting genuine interest in values-based purchasing. Furthermore, the documents uncovered during this lawsuit illustrate the deception of Hormel’s messaging, offering fuller answers to the questions that might appear in a media guidance document.

The animal agriculture practices throughout Hormel’s supply chain and their effects on animals and workers – in Hormel’s own words – are grislier than previously understood.

The way animals were raised for Hormel’s products is shocking, even putting aside questions about the use and misuse of the term “natural.” Because the animals and production practices used in the Natural Choice line were virtually the same as Hormel’s other products – like canned chili or Spam – internal documents we uncovered during the lawsuit demonstrate both the deceit of Natural Choice advertising as well as the more general offenses of Hormel suppliers’ meat production.

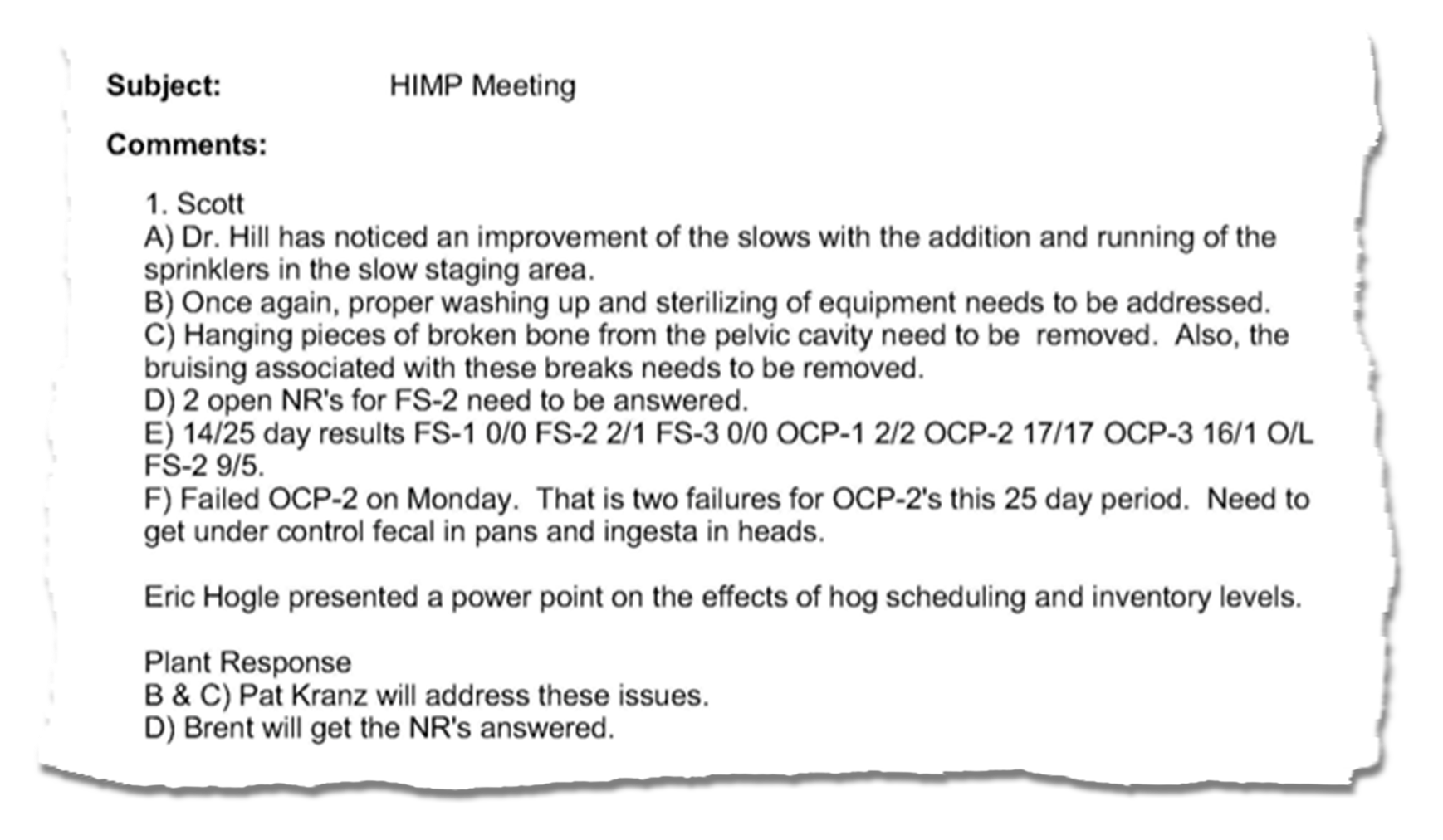

For example, we discovered that Hormel had food safety violations related to conditions that were anything but what could reasonably be considered natural. Violations included, but were not limited to, contamination of carcasses with “fecal material, ingesta, and milk” (coded “FS-2” by FSIS), failure to address bruises, sores, and other unsightly wounds and infections (coded “OCP-3”), and failure to wash and sterilize equipment (Exhibit 96).

Read together, these documents reveal a pattern of violations that pose threats to consumer health and to workers in these plants. The following sampling from noncompliance reports uncovered during the lawsuit shows feces on carcasses on their way to being processed into Hormel products.

Each noncompliance report that FarmSTAND uncovered for one facility ends in a similar way and shows how ineffective Hormel was at addressing the presence of fecal matter on the meat. “The establishment’s preventative measures for controlling fecal material from entering the chiller have not been effective or have not been implemented” (Exhibit 102). One month later at the same plant: “The establishment is not preventing fecal material from entering the chiller” (Exhibit 99). Five months later at the same plant: “The establishment management is not preventing carcasses with fecal material from entering the chiller” (Exhibit 100).

As a part of this lawsuit, FarmSTAND collected sworn testimony from Hormel employees to reveal contradictions in the company’s claims to naturalness. In one deposition, Hormel Director of Procurement Cory Bollum confirmed Hormel does not require suppliers to phase out inhumane housing methods or to provide pigs with access to the outdoors or pasture (Exhibit 208). An instruction manual for Jennie-O, a Hormel-owned brand, revealed that animal growers were required to stimulate “unnatural” conditions, like forcing turkey hens to live in 24 hours of light a day so they eat more and grow faster (Exhibit 142). Another Jennie-O slide deck explained how turkeys are raised in “all confinement,” as opposed to a free-range setting that consumers are likely to associate with products labeled “natural” (Exhibit 143).

Beyond baseline conditions, more acute mistreatment of animals by Hormel and its suppliers separated their meat from what most consumers would believe to be natural. Examples abound. In one instance, a line stop at a processing plant caused 150 chickens to suffocate to death (Exhibit 211). And their pregnant and nursing sows are confined in particularly cruel ways. Pregnant sows are confined in tight barred metal stalls called “gestation crates,” which were barely larger than the animal and “restrict ‘normal’ behavioral expression” (Exhibit 147). Once the sows give birth, they could be then forced onto their sides unable to move naturally in barred metal crates called farrowing crates (Exhibit 207).

FarmSTAND also uncovered slaughter and surgical practices used on animals in their Natural Choice line. Hormel’s suppliers used manual blunt force trauma – a deadly blow with a dull object to the head – to euthanize their suckling pigs (Exhibit 208), and chickens were crushed to death as a form of euthanasia (Exhibit 211). When asked whether pork used in Natural Choice products could have been sourced from piglets who received no anesthesia when they were castrated and had their tails docked – cut off supposedly to keep pigs from biting each other’s tails – a Hormel representative answered that “since that’s a common industry practice, yes” (Exhibit 207).

If you are interested in learning more beyond this litigation, ALDF conducted an undercover investigation of a pig supplier it identified as providing animals to Hormel and you can see coverage of that footage here.

The lack of regulation in advertising – coupled with regulatory loopholes – create false consumer expectations regarding chemical and additive use in “natural” foods.

In a Natural Marketing Institute slide deck presenting an industry study on consumer beliefs about what ‘natural’ means, 86 percent of the general population surveyed believed natural foods should have no added growth hormones, and 72 percent believed they would be antibiotics free (Exhibit 51).

But documents FarmSTAND obtained from Hormel suggest a wide gap between consumer expectations about the use of potentially harmful chemicals and antibiotics in “natural” food versus how Natural Choice meat is actually produced. Pigs that became Natural Choice products were not tested for ractopamine, a drug that promotes muscle growth and is associated with broken limbs and a complete inability to walk – and was banned in 160 countries as of 2014 (Exhibit 208). For the purposes of sanitation, chicken carcasses in at least two facilities that supply Hormel were washed with either chlorine or peracetic acid before being processed (Exhibit 211). Termin-8, a feed disinfectant that contains formaldehyde and propionic acid and is used for its antimicrobial properties, was incorporated into feed for turkeys destined for Natural Choice products (Exhibit 213). A letter authorizing export of meat to Russia confirmed the allowable use of growth-stimulating antibiotics – bambermycin and/or virginiamycin – in Hormel products (Exhibit 138). Guidance material for Jennie-O turkey producers, a subsidiary of Hormel Foods, showed “mixing appropriate water disinfectant or medication for the flock” as a daily chore, and included a picture of cramped conditions (Exhibit 142).

A: The USDA has approved the term on our packaging and we extend the — we extend the use of the word from our packaging to the advertising.

Q: Why choose to advertise the products in that way?

A: We advertise it with “natural” because we believe that’s what consumers are looking for… we found that “natural” is a way to differentiate our products versus some of our competitors, so it stands out.

— Rule 30(b)(6) Deposition of Jeremy Zavoral, speaking as Hormel Foods, Exhibit 217

Widespread use of antibiotics in raising food animals, standard among Hormel Natural Choice suppliers and across the industry (Exhibit 208), “contributes to the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria” and poses real risks to public health. Unsealed documents reveal positive tests for foodborne illness-causing pathogens among products, like Salmonella (Exhibit 86, Exhibit 87, Exhibit 88, Exhibit 111, Exhibit 112, Exhibit 213).

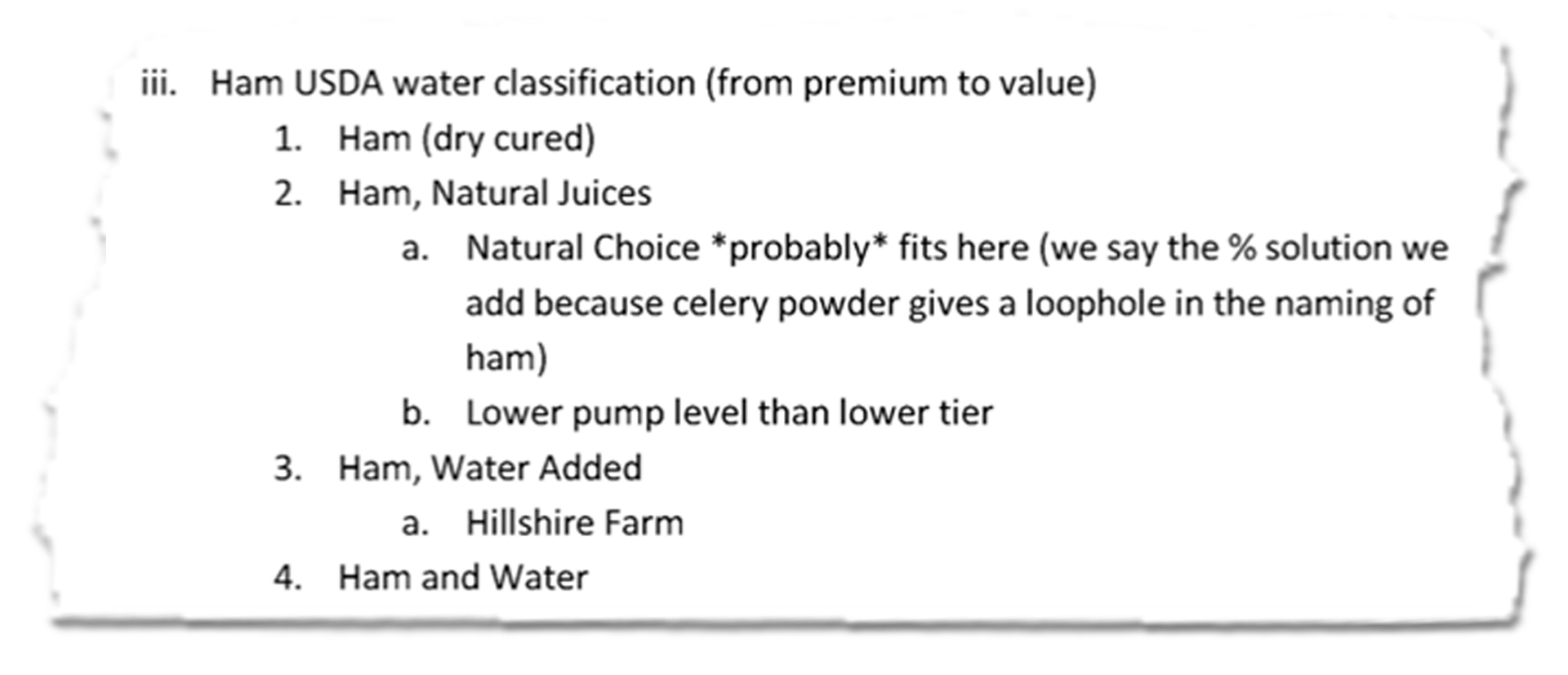

The documents also point to various loopholes that the industry uses to comply with the letter but not the spirit of the law. One such loophole has to do with the use of celery powder as a preservative that, only after it is added, produces nitrates that then extend the shelf-life of a product. Companies can claim such products have “no added nitrate or nitrite, except for those naturally occurring,” although according to scientists and advocacy groups, there is no evidence that using processed celery ingredients is healthier than other added nitrites. While Hormel claims they use celery juice or powder to get “that cured color and cultured flavor,” (Exhibit 209), one of their own documents says it “gives a loophole in the naming of ham” (Exhibit 116).

This loophole does not just allow the company to skirt a regulation; it allows one more way to mislead consumers, as Hormel’s own Consumer Insights Supervisor stated that many “consumers think [natural] means that there’s no preservatives in it” (Exhibit 212). (FarmSTAND and the Animal Legal Defense Fund submitted a regulatory comment to the FDA challenging that loophole.)

To sum up, the practices used to create Hormel’s Natural Choice line of products do not represent the types of practices a consumer might expect from its “natural” branding. While one might expect Natural Choice products are the result of safer and more humane practices, a Hormel official confirmed that it “would be true” that there’s no separate manner in which the pigs raised for Hormel Natural Choice are raised versus any of the other Hormel-branded products. (Exhibit 207)

These business-as-usual practices—the factory farming and the lying about it—raise serious concerns about traceability and transparency.

Hormel exploits both the government’s failure to comprehensively regulate use of the term “natural” in advertising, and rising consumer interest in organic foods (Exhibit 51) to generate consumer confusion. In so doing, Hormel brands meat raised with low-quality production methods that don’t meet consumer expectations of what “natural” means, and sells those products at highly competitive prices. This undercuts producers and companies who are using animal rearing and processing methods that actually meet these consumer expectations who may charge a premium to cover the costs associated with those practices.

For example, a manager of the Natural Choice brand informed multiple senior members of Hormel’s marketing staff that “[c]onsumers assume natural meat is antibiotic free,” even though the exhibits examined above illustrate how antibiotics and other growth-promoting additives were a standard feature of Hormel suppliers’ growing practices (RSUMF, para. 84). This deception, and the practices masked by it, reveal a pressing need for reforms that make food systems more transparent in ways that can bolster animal welfare, worker safety, human health, and environmental sustainability.

The uncovered documents also challenge whether existing regulatory frameworks for food safety can or will be effective in grappling with the scope of Hormel’s harms. While a consumer might reasonably expect regulatory agencies like the USDA to confront the problems posed by Hormel, oftentimes its programming perpetuates those same harms.

The Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points-based Inspection Models Program (HIMP) is a case in point – a “food safety program” that sped up line speeds and served to increase processing of pigs for pork. In Hormel’s view, “The HIMP program is designed to allow the USDA inspectors better perspective and more flexibility to monitor activity and identify any issues. In addition to the USDA inspectors at the facility, there are employees trained to the standards of the UDSA conducting the additional inspections” (Exhibit 109).

While corporate actors like Hormel claim that the HIMP program gave “more oversight, not less,” food safety advocates including federal meat inspector whistleblowers have argued that the program poses real risks to public health and is “USDA’s way of catering to the industry instead of the consumer.” Despite this, HIMP was the basis for the USDA’s New Swine Inspection System (NSIS), which has received similar flack. The line speed increases authorized under NSIS were then struck down by a court, but USDA is still authorizing plants to operate at increased speed. (Public Justice represented members of Congress who detailed their qualms with NSIS in an amicus brief.)

Q: And nothing in your contract actually requires lifecycle auditing from cow-calf through slaughter?

A: Correct.

— Rule 30(b)(6) Deposition of John Hilgers, speaking as Hormel Foods, Exhibit 211

FarmSTAND and ALDF’s suit showcases the need for consumers to have transparent and accurate information about where their food comes from and how it is made so they can opt for products genuinely developed in line with their values regarding human health and safety, animal welfare, and environmental impact. It also makes clear the limitations of consumer awareness as a driver for change when companies are permitted to use advertising to create confusion and manipulate customers into believing their products are something they are not.

Lastly, it underscores the importance of holding corporations accountable for their active exploitation of the regulatory gaps that perpetuate harm to humans, animals, and the environment at a massive scale. Litigation is one tool among many that can be used in service of and in solidarity with frontline communities who are transforming the food system. We hope that materials revealed through discovery offer important data for further efforts to increase transparency and accountability in the food system.

Check out the briefs that compelled discovery in this case and explore unsealed discovery materials below.

Illustrations by Tania Lee.

The following exhibits were all made public via court order. All exhibits were made public on April 8, 2019 when the court granted ALDF’s March 5, 2019 consent motion to unseal documents that Hormel did not move to seal, and unsealed “the excerpts of the transcript of the deposition of Wayne Farms’ Rule 30(b)(6) witness and the documents produced by Wayne Farms that ALDF submitted with its summary judgment motion” (Exhibits 175 and 216). The case docket can be accessed using case number 2016 CA 004744 B here.

While no party appealed the ruling unsealing documents, ALDF appealed the trial court decision granting summary judgment to Hormel. The D.C. Court of Appeals, the highest court in the District of Columbia, subsequently reversed. That decision both establishes public interest organizations have standing in the District to protect consumers and despite federal law regulating meat labels those rules do not preempt claims against false advertising. Animal Legal Def. Fund v. Hormel Foods Corp., 258 A.3d 174 (D.C. 2021)